I walked up Anapafseos Street (Eternal Rest Street) and through the grand entrance. The scent of nature – of being surrounded by trees, moss and flowers – and burning incense hit me as I carried on into the depths of the First Cemetery in Athens. White stones among green growth, the noise of the bustling city completely muffled in the distance.

Whenever I travel, I enjoy visiting cemeteries. They are a stark contrast to the liveliness and the colours of the city streets with their street art, the half-torn posters still glued to walls, the sounds of sirens and roasted chestnut vendors and impatient drivers. They are peaceful, clean places full of history and stories and silence. They are otherworldly.

I’ve walked through most of the largest cemeteries in London and some of the smaller ones. I’ve seen Jim Morrison’s simple, flower-strewn grave in Père Lachaise in Paris and Oscar Wilde’s more extravagant resting place spattered with lipstick kisses and lined with a row of glimmering tea lights. In St. Lucia, we saw pink gravestones. In Copenhagen, Assistens Cemetery is one of the most beautiful. I’ve walked through war cemeteries in Boston, seen the crumbling, centuries-old stones in rural Scotland and tiny ramshackle graveyards in small Colombian villages.

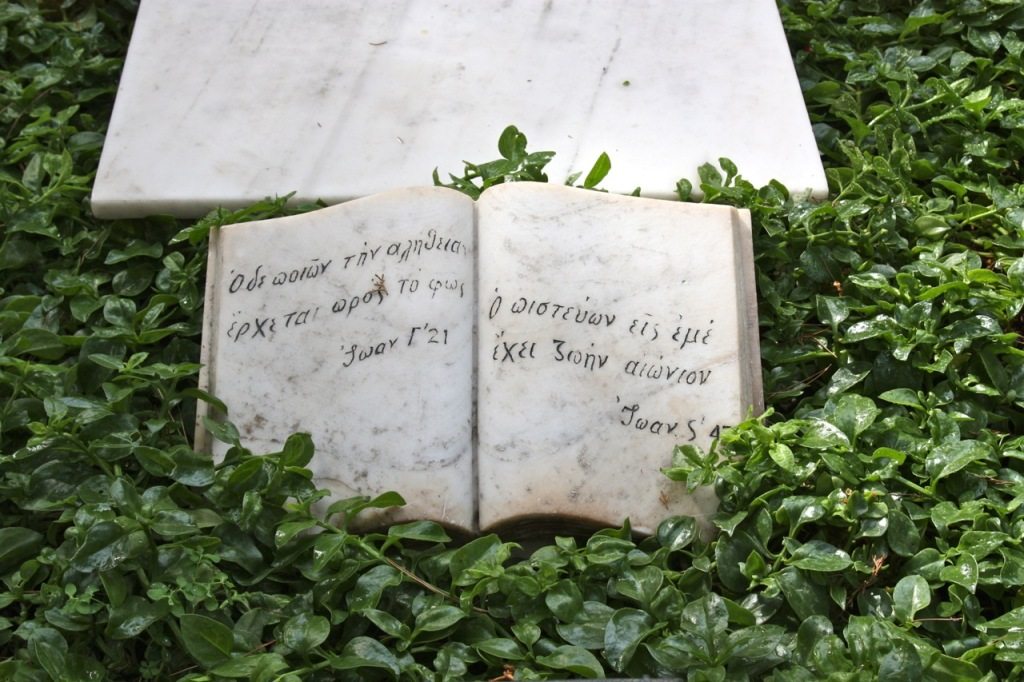

You can learn a lot about a culture through the way they bury their dead, how they later pay their respects, the colours and trinkets and words you find throughout a cemetery.

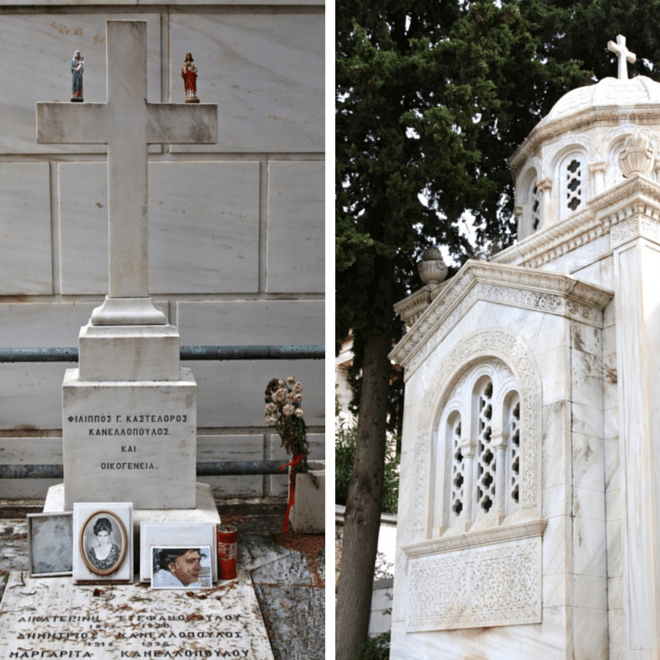

The First Cemetery in Athens is completely surrounded by walls. Many graves had candles burning and small olive trees nearby that were probably planted at the same time the person was buried. Cypress and pine trees line the pathways, casting long shadows.

Cats curl up on gravestones, sleeping or watching for the stray mouse to scurry past for dinner. It was empty of other living people apart from three widows, dressed in black, walking alone. You can hear the constant song of birds.

There are nods to the neoclassical architectural style of Ancient Greece among the tombs with columns and choragic monuments. While many of them are simple, others are strikingly lavish.

I passed one mausoleum that was inscribed with Trojen War scenes. A sculpture of a sleeping girl topped the grave of an 18-year-old who died of tuberculosis. This is the work of Yannoulis Chalepas who was one of the most famous marble sculptors of his time, an artist from Tinos who unfortunately suffered a nervous breakdown and many suicide attempts during which time he started to destroy some of his own work. In the sleeping girl’s hand, there is often a fresh flower.

There are other many children and teenagers and young people buried there and it’s easier than usual to imagine them alive as a great number of graves have framed photographs on top in memorial. There are also politicians, architects, film-makers, composers and poets like Giorgos Seferis who wrote:

“Now I can’t hear a sound.

My last friend has sunk.

Strange how from time to time

they level everything down.

Here a thousand scythe-bearing chariots go past

and mow everything down.”

There are many family graves, carefully tended. Others are left in the hands of mother nature, now surrounded by a sea of plants and flowers growing from the earth rather than picked up from the local florist. Some are also covered in moss which is probably a sign that, in the case of a family grave, the last to be buried could have been the last in line.

At the end of the cemetery, I climbed up a crumbling set of stone steps and I was rewarded with an unexpected magical view over the city at the Acropolis at the center.

It’s a hauntingly beautiful place and well worth a visit if you ever find yourself in Athens.

You are so right, we can learn a lot about each culture through the way those cultures bury their dead. This post made me realize that I need to visit more cemeteries. I haven’t been to one is a very long time. Hope you are having a lovely day so far, sweetie.